Cheung-Ang Siew Mei, JP

Occupation: Executive Director – Christian Action

Born: 3 March 1960, Malaysia

Resides: Hong Kong

Interview date: 14 September 2013, Hong Kong

From 1983 to 1997, from the UK to Hong Kong, Cheung-Ang Siew Mei had worked with thousands of Vietnamese boat people. She had managed a number of important programs to assist Vietnamese boat people in open camps, closed camps, transit camps and to detention centres. She had held key positions with various organizations such as: Save the Children, the UN and Hong Kong Christian Aid for Refugees.

History of working with Vietnamese boat people

1st position – 1983

I was in the UK when I decided not to return to Malaysia, instead I stayed and pursued my calling in life as a Christian. I felt that God wanted me to be involved with justice and compassionate work. There was opening available to assist Vietnamese boat people resettle in Liverpool. It was a full time volunteer job, and I was paid 50 pence, as lunch money every day and a free bus pass.

My job was to make them feel welcome, get them furniture, take them to the doctors’ and take their children to school, bring them to hospital and basically act as a translator. That’s how I began, and I was acquainted with Vietnamese friends for three years.

Then I got married and came to Hong Kong.

2nd position – 1986

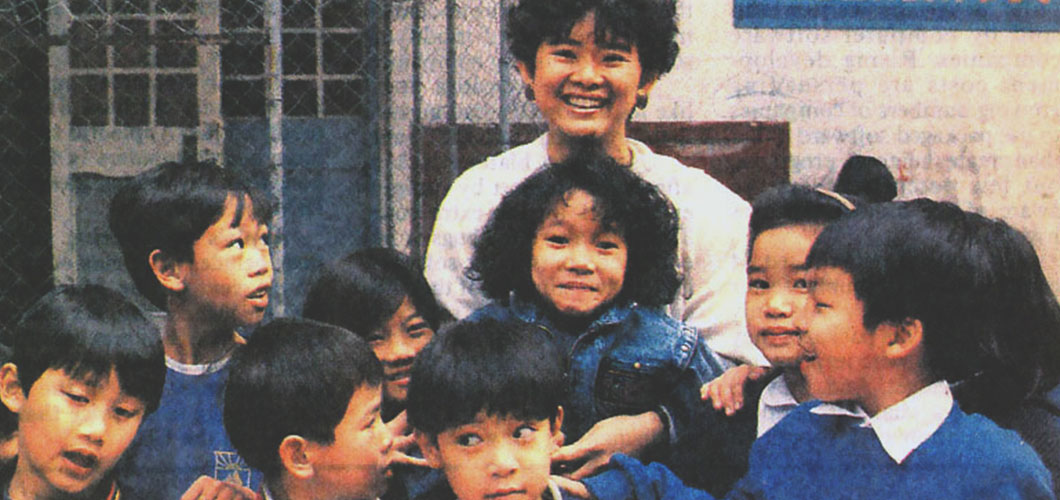

While in Hong Kong, I was very attracted to the Vietnamese refugee camps for the fact that these were the camps where the people and individuals I had served had come from. Again, I felt the calling to go and serve in the camps. I started working in Tuen Mun camp. It was a closed camp and I worked as English teacher, and the first agency I worked with was ‘Save the Children’. In the camp, people were very friendly, the children were very happy to have me, a young teacher and with Asian origin.

I spent five days a week in the school. I would start at 8:30am and finish about 2pm, and then I would stay back until 4-5pm socialising with them. I created a room where they could just come and hang out. Sometimes I brought bring them some biscuits or something to munch.

I played the guitar and so I brought music to the camp. So I stayed back and brought them guitars and we sang songs and one of their favourites was ‘500 miles’. And so it was really nice and I was very happy that part of my interests and talent could get transferred to children. And when the whole camp was singing ‘a hundred miles, a hundred miles’, you know, it was a very special feeling, because there’s nothing to do in the camps. So when they could sing and learn to play the guitar, it brought about a different atmosphere in the camp.

I was only 26 then, there wasn’t much of an age gap between the students and me, so I really enjoyed my time there. Of course I taught other things apart from English. And I became their friend and they could talk to me.

But I can’t help feeling the sense of a waste of a life. I remember I was very mean to a kid, who didn’t come to school, and I went to his unit in the camp and looked for him, and I felt so angry. I remember this little boy named Toi. I said to him, ‘Toi, why aren’t you coming to school to learn something? What can you do here but eat, sleep, play?’

3rd position – 1986

After six months, I was head-hunted by Mr Farrow from the Hong Kong Christian Aid for Refugees, which is now Christian Action. He asked me to run an orientation program to orientate Vietnamese before they go to the UK. For a few months I provided orientation classes telling the refugees what to expect, and I had contact with the people in England, so that I would tell them up to the point of who would be meeting them in England.

4th position – 1987

Soon I was given another project that was funded by the Rotary of Victoria. This was a bigger and one of my milestone projects. In this program, my job was to get the young people away from the factories. They were very talented but in the camp they were losing interest and so they would go to the factories to earn a living. Working in the factories was a big thing at that time from 1986 to 1989 because there was a shortage of labour, and the Vietnamese refugees could earn a lot of money.

During that time, the young people were either gone to the factories or become a ‘pickpocket’ or work as a coolie. My job was to steer them away from those directions. I placed them as interns with the Rotary Club members. They would be going to an Architecture firm and they would learn to be a trainee draftsman or a receptionist. Or put them in a hotel where they could become a bellboy or a waiter. In the meantime, I taught them manners, etiquette, basic English and basic computing skills etc.

I would go to Apple Computer and get the Executives to become volunteers and they would bring their Macintosh – at that time Mac was very big. And they would bring their Macs and teach them to do basic programming. The young refugees really enjoyed that because the people that came with them were very intelligent. Then the Rotary Club members would offer them jobs. “The Rotary Club of Victoria, who sponsored the project received an award for it being one of a great and successful project.”

5th position – 1988

A year later, there were changes in the policies, closed camps would be diminished and Vietnamese boat people were to be kept in either open camps or detention centres. Then there was pressure to find jobs for the Vietnamese refugees plus the pressures from the community and local district offices that against the idea of having Vietnamese people come out of the camps. So the UN picked me to manage the project. That’s when I knew Carrie Yau, she was the Principal Assistant Secretary and she needed to push this project. There were a lot of barriers; one of the barriers was that the Vietnamese refugees couldn’t leave the camps unless they had a job, and sometimes if they didn’t have money they would commit crime.

But thank God! God is very kind, it was the labour shortage. So I would find busloads of jobs in bra-making factories, jeans-making factories, making of materials and those sorts of factories. And all sorts of people would come knocking on my door saying they wanted to hire Vietnamese refugees. So I was like a placement agency and I had teams of people placed in the camps for the recruitment process and then I organised volunteers to do orientation about things like the toilets and how to use them – i.e. the toilets outside aren’t like those in the camp, this is how you use it, don’t squat on it, sit on it [laughs].

All those little things we would take for granted!

I was very overworked and overwhelmed, because I was very young – in my 20’s – and having to face all the politics of the Districts, the UNHCR and the Correctional Services Department (CSD) etc. But I guess I’m not the stereo-typed Social Worker, so I got on quite well with all parties. I was well-received by the Vietnamese, the CSD, the Government, the local district councillors. So they would always joke and push me forward because I was such a stranger and they didn’t know what to expect. And I would always ask very direct questions and answer very directly because I wasn’t afraid to put forward some points.

I negotiated with the factories to sent buses to the camp to pick up Vietnamese refugees to their factories to work. Many of the refugees know basic Chinese; especially those who lived in the closed camps watched Chinese Television. We gave them orientation, with basic Chinese training. I also hired some of the young people I trained before to be the translators and interpreters.

“It was too big for me probably, but that’s God’s will. And so I headed a team of people to find jobs for all these refugees. I think there were probably 8000-10000 people in the closed camps.”

After one year I worked so hard I had and ulcer and had to stop.

6th position – 1992 – 1997

Based on my previous successful track records, I was once again recruited by Hong Kong Christian Aid for Refugees to be a Project Manager. The new project was placement and the training, and cottage industry projects in all of the camps.

I was managing multiple camps all in the detention centres. Each camp would have a team run by us; cottage industry and training programs were also run by us.

At that time EU was given out some grants. So we taught some of the Vietnamese basic accounting and how to write business plans, so they can apply for funding.

I quickly became Program Director, and then in a very short time, I became Director of the Agency, in November ’92. I then moved to a more strategic role and got some very good people ran the programs. One of them now is Head of some Regional Division in the UK. And Nigel Priess was my Manager during this EU project and training, and now he’s one of the Immigration Directors in Australia.

We ran programs for two groups of refugees; one was in the open camps and one was in the detention centres. We ran the pregnant women’s program next to Kai Tai camp, and we also had a dental program, a program for unaccompanied minors.

Q: What can you tell me about detention centres?

A:I have to say that people can get exploited easily in the detention centres. I think in the past they were somehow smuggling in drugs and you would hear stories of even UN Officers exploiting the refugees, and even CSD Officers exploiting the women, and the Big Brothers etc. But all that is hearsay. I can’t help but realise they are very vulnerable in the detention centres. In the camps, it’s all concrete the huts are hot, there’s no privacy, there might be a whole family in one bunk with someone else in the bunk above, there’s no dignity. For me this was the issue.

Q: Was it lack of facilities or a deterrent?

A: I think there’s a lack of facility. They really had to build the new places from scratch; they had to make it ‘prison-like’ but it wasn’t a prison. It was very expensive when a whole lot of people need to be hired to guard the refugees, feed them, school them, and create activities for them. And Hong Kong being so small, and with the Hong Kong people themselves living in small places, it’s understandable but not acceptable. So they don’t have a choice but to get Prison Officers to look after the refugees.

Q: Did you ever witness any riot in detention camps?

A: We were concerned that people were taken against their own will. So the Government allowed us to monitor the process. We were the first agency to volunteer, because it was very political. People don’t like the forced repatriation. But for us, we knew it was inevitable. So we made sure it wasn’t violent or unfair. Of course we had to chase them because they were running and hiding.

The most memorable thing I saw with my own eyes was the forced repatriation at Whitehead Detention Centre. We were up in a high place, looking down and writing notes. The Police were chasing them because they didn’t want to go back. Some of them had to be carried or dragged out. And so it wasn’t very nice to witness.

One of my staff members, my manager – his name was Adam Voysey – one day he came back and was crying because he said he didn’t want to see these things. He spent a lot of time at the front line, and one time he witnessed where they threw tear gas.

I went with the UN team to Vietnam to see for myself that the Vietnamese refugees are not persecuted. We had a list of people we would visit, by surprise; some were the people who had received grants. Most of them were doing ok. So after my trip, I was quite at peace for accepting the fact that some of them have to return to Vietnam.

Q: Was there any moment when you thought you have had enough and wanted to quit?

A: I think when I had an ulcer. Obviously it was physically hurting and that was because I was so young and had so much responsibility and so many demands. As personality, I just wanted to get it done quickly. And how quickly can you get it done when the community is so large? I had no training, but yet after two years away, I kind of missed it. I went back to my mentor – the guy who hired me for the Rotary program. He asked me to come back, and I believe God was saying to me to go back, and because there was some corruption. I didn’t like the idea of money not being spent properly on the refugees; exploiting the vulnerable and the weak. And I agreed to go back and I’m glad I did. And shortly afterwards I got the job as Director, which lasted until now.

Q: What were some of your most memorable moments or stories?

A: A story about my predecessor, whom I’ve never met. He set up Hong Kong Christian Refugees. One day a boat came, this man emptied the vocational centre to allow them the Vietnamese refugees to stay there. So one time at the training, the Director of the Hong Kong Christian Service mentioned him and said that, ‘you can’t do things the same way; you have to change them in every era’. He said that his predecessor put all the refugees into the vocational training centre; you can’t do that now because you have to think of Health and Safety etc.

It was the first time in my life in Liverpool that I encountered refugees but I had no idea about their experiences.

Once, a young man said to me, with no emotion, ‘I was forced to fight the Chinese on the border and we had to throw a grenade and we would see body parts flying everywhere. And then we were caught, and we had to fight with the Chinese against the Vietnamese.’

It was horrendous. I mean, he didn’t die, but he saw all the horrors of war and was caught and had to fight on the other side. And there he was in Liverpool which is cold and unfriendly and nothing like Vietnam.

One of the sad things, from my observation was that single men and single women were kept in separate sections. It was so artificial, but if they didn’t do it that way there would be a lot of problems. And that situation created some homosexuals. It wasn’t even talked about. But it was there, because at the time, it was a very ‘hush hush’ phenomenon. It was just too bad and such a tragedy that they had to flee Vietnam for whatever reason. And for me, I don’t judge economic migrants. Because I think we are all economic migrants of some sort when we go to another country to find a job or resettle. I mean, Hong Kong people go to Canada, they migrate there. We are all economic migrants. But even right now, in Australia they are so hostile towards people who want to have a better life. There is nothing wrong with wanting to have a better life. There is nothing wrong with wanting to run away from Iran or Afghanistan or anywhere.

Q: Do you think the Government could have handled it differently?

A: To receive so many people, I think that the Hong Kong Government is one of the most decent Governments in Asia. They didn’t turn anybody away, they didn’t shoot at anybody.

One thing regarding politics, the reality is in Hong Kong a lot of Mainland Chinese people wanted to come over, and the Government was so strict about it, if they were caught crossing the border, they were detained and repatriated. Even right now, the Government’s hands are tied. They cannot be too kind to refugees from all over the world, whereas they have very strict rules for their own people. For the dilemma that they are in, the Government handled it very well. They are kicking out somebody’s cousin or friend – your own people – yet you are expected to embrace and give others a fine life. It’s very complex.

More credit should be given to the Hong Kong Government and the people who looked after them – or even the people who monitored them. There are bound to be ‘bad hats’ everywhere. But I do believe the majority of Correctional Services staff was ordinary and kind people.

Q: What was it like for you at the end?

A: In a way I was relieved that it came to an end.

Q: What was this whole experience with the Vietnamese boat people mean to you?

A: I did not choose any communities – God chose the communities, and I think that was a time in history when human suffering was very prominent, and then the running away from persecution. So I felt happy that I had a part to play in alleviating the suffering and providing a helping hand to people who had gone through so much.