Bonnie Wong

Retired

Born on 21 May 1950 in Hong Kong

Resides in Hong Kong

Former Prison Officer

Interview date: 11 November 2012, Hong Kong

Interviewer (I): Please tell me about your involvement with the Vietnamese refugees?

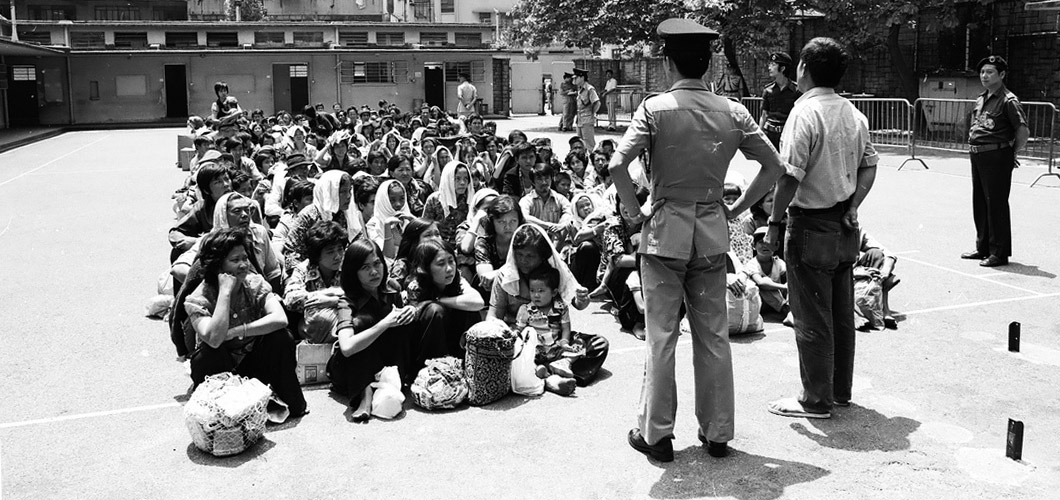

Bonnie Wong (BW): I am a Prison Officer by profession. In late 1978, there were some small boats coming to Hong Kong, which the Government needed to settle. Somehow the Department undertook the work to take care of those arrivals. Because the arrivals contained family members – men, women and children – when opening a center they needed some women to be on duty to take care of the women and children’s side of things. So I was one of the women posted to run the newly set-up center for the Vietnamese arrivals. And in those days, women and children were housed in one section and men in the other section. So family units were separated in this way, and I was in charge of the female section.

I: When you first started up the camps, how many refugees were there?

BW: At that time there were four dormitories, two dormitories for men and two for women and children. The place used to be an addiction treatment centre for young drug addicts who were below the age of 21.

I: Was it difficult to manage them?

BW: It was different, because in running a prison there are lots of rules and standards to follow. But we were not in charge of children at all, except babies of female prisoners up to the age of three. So it was very different. It is a new experience and it is not like running a prison or a detention centre where everything was systematic for adults whom you expect to be able to understand the rules and follow them. But when it comes to family members, like young children, it’s a completely different picture altogether.

I: Were they considered as prisoners?

BW: No, they were not. They were people under detention. In other words, they can’t go out to the community freely, but of course while they were under detention, they would need to be taken care of, clothed, fed, kept warm and that sort of thing, medical care etc.

I: What were your day-to-day activities?

BW: There cannot be a lot of activities. In a normal prison or detention centre, we had to provide work for the adults. But in those circumstances, our work involved space and also equipment and all the rest of it. So at that time, we couldn’t really provide a workshop so to speak for them. So their daily activities were managed from when they woke up. We served breakfast first and afterwards they were expected to clean up their own dormitory and public areas. And then basically they were free. We would try to provide some sort of work for them, if they can [work], but at that time they were all being organised. It wasn’t something that was very well organised, put it this way. For the children, we tried to set up some education classes for them with the Head of Voluntary organisations and that type of thing. We tried to meet the needs of all concerned as far as we could with our limited resources.

I: What were your main duties in regards to the Vietnamese refugees?

BW: The incident was custodial. We were there to keep them in[side]. But the word ‘custodial’ could mean ‘providing them for 24 hours a day, their daily necessities for that period’. That is to say, they had to be fed; they needed accommodation, clothing and bedding etc. To provide them with the basic necessities of what a person needs in daily life.

I: How many staff did you have supporting you then?

BW: I have to check the records, but there were two sections – one for men and one for women. For the girls, I have to check the Departmental records as I cannot remember. But it was a reasonable number I think.

I: How long were you in this position?

BW: A few months only, but then another big boat came. The ship’s name was Huey Fong, accommodating thousands of Vietnamese people. They arrived in Hong Kong and I think it was December 1978. And the Government decided to open a camp to house these people. And I was again assigned as one of the Officers to start that camp. So I got posted to that camp in January 1979 to start receiving the Vietnamese people from the ship, Huey Fong.

I: On average, how long did each refugee stay in the detention centre?

BW: We didn’t know. At first, we thought they would be treated as refuges. And that eventually some country would take them [on]. But later, we found that wasn’t the case, and some of them could be detained for years. And others could be taken to other countries as refugees. So as the situation developed and changed, some could be detained for quite a long time.

I: Do you have any idea what the longest time a refugee could be there?

BW: No sorry, I’ve lost count. But I think somebody would have some idea. But the first lot I believe, most of them have been resettled in other countries. It was the others that came later that encountered problems.

I: So the second time when you were asked to work with Vietnamese refugees, was it easier for you because you had some experience?

BW: It was a completely different thing again, because from what I understood, the Department was asked to take up the responsibility of running the camp. But our then Commissioner refused. I believe on the ground that the resources given to us were not good enough to run a decent place [for the refugees] to detain people. Because we firmly believed that in order to detain people, there is the need for sufficient facilities. You have to provide work for them, education for the children, physical activities for them and it’s a whole range of activity. All these things need space, equipment and staff. But Government at that time was unable to provide all those resources. And I believe later that it came to an agreement that the camp would be set up under the Policy Branch – the Security Branch. And be manned by joint forces, which were then the Prisons Department, which is now called Correctional Services Department, the Police and the Civil Aid Services.

The main division of job was that the Police would be responsible for security, basically perimeter security to prevent outbreaks etc. And the Civil Aid Services would be responsible for the distribution and allocation of dormitories and sleeping spaces, while we would be in charge of the internal management of the camp. So it was a joint effort of the three services under the Security Branch. So it was a completely new thing. First of all, there weren’t any rules for the camps, nothing there for us to follow, we didn’t know who the Authority was and what was allowed and not allowed. So we had to figure out these things and take their status into consideration, the children’s needs and rights etc.

So at that time, we started drafting the basic rules and regulations for them. And other Departments would be responsible for drawing up the new scale for them, i.e. what they should have and the times etc. So basically, it was starting from scratch. We had to develop a new thing from our own experiences and taking into consideration the current circumstances. So it was a completely new thing.

I: Were there any riots?

BW: Not during my time, but eventually there were lots of riots and uprisings, or confrontations which came at a later date.

I: How long were you involved with the Vietnamese refugees?

BW: These were the times when I was on the frontline. But as time went by and I moved to other jobs, in one way or another, I got involved with the Central Administration for the Vietnamese [boat people]. Or until all the camps were so-called, the issue was basically finished in about 1997-98. So in twenty years, I was in some way or another involved, in overseeing the camps and things like that.

I: You probably have had both fond and unpleasant memories in dealing with the refugees?

BW: It cannot be said as fond or unpleasant. It was just part of the work, which was different and not something a Career Officer would accept.

Second interview

BW: Detention. People would associate it with the Middles Ages, where you would talk about brutality and those sorts of things, but it is not this at all. We are talking about handling a group of people who are not willing, or who may not necessarily be very happy to be handled by you. [They are in detention] Not of their own choice. But at the same time, you have to provide their daily basic necessities for them to go on in humane conditions.

When I say humane conditions, I mean the conditions of the current time of the local people at that time. It differs from country to country, race to race and nation to nation. A person from Cambodia, their basic conditions may not be the same as the basic conditions of someone from the United States. So we are talking about providing a person to live in a decent environment, appropriate at that time and place. And it is not a question of ‘fond’ or unpleasant memories.It is something that is completely different – we are handling a completely different category of people.

It’s not like somebody who offended the Law whereby there are already laws and rules to govern their rights and otherwise. What you can or cannot do. But here, you have to basically work out, or figure out… for example the basic rights of children and the UN’s rules of all these different categories of people. And then try to provide with your own resources [what is required] to meet these standards. These may not be met all the time, but you have to find help.

For example, in these camps, you have to involve voluntary organisations like classes for children that would be run by ‘Save the Children’ or some charitable organisations like Caritas to run educational classes. And you cannot force them to work, and it has to be on a voluntary basis. And also, in a word, you have a lot to handle, or a lot to learn and it was too busy to consider whether I liked it or whether it was pleasant or unpleasant. There were a lot of new things coming in that we had to pick up.

I: Were there any incidents that stood out for you over the years that you still remember?

BW: Oh yes. When you see the conditions when they come in, you feel very sorry for them, and at the same time feel very annoyed. For example, when food was being prepared, the whole group would come and snatch the food. They wouldn’t queue up and that was annoying. We tried to distribute one portion to each person, and then suddenly the whole group of people… and the situation would run out of control. There were a couple of occasions when there was no food at all because it was all snatched. So the situation was eventually brought under control when food was being issued, I took a walk around the dormitories. And I saw some women and children playing in their dormitories. And I was surprised and asked them why they weren’t queuing up for food. And the woman with two or three children said, ‘somebody is taking the food for us’. And I asked who that was, whether it was her husband. She said her husband had died in the war and a ‘friend’ was lining up for food for her. And she couldn’t tell me who this ‘friend’ was. So I asked her to come with me and went into the food issuing area. And I asked her to point out the man to me, and I made sure she got the food before I left. So I think sometimes you have to be careful, you just don’ know what sort of things could exist in the camps.

And then you just by accident, sometimes when you walk around, you find out there might be something wrong. You have to take care of these things, such as another occasion where I saw a worried mother with a baby with a black face, a greyish complexion. I asked what was wrong with him, and the mother said he was very ill. I wasn’t a medical staff and had no knowledge of medical conditions. I went to my senior who is a nurse by training and asked him to examine the baby. My senior said the baby was in a serious condition and needed to go to the hospital on Lan Tao Island. And then by our own understanding, I asked for the mother to be sent as well. Who had the right to sign a consent form for the baby? Not us, only the mother, so the mother had to go with the baby. And the baby was admitted, and he was in a critical condition. But he was eventually cured, and eventually made well. So that is the type of thing that happened in a camp [setting]. And the mother herself didn’t really know [what was wrong]. She knew that her baby was ill, but she didn’t really know how bad the condition was. And those were the type of things you had to look into, and the people running these detention centres have to take note of these [kinds of things]. And that’s why we need medical staff and the rest of it; otherwise it’s a matter of life [or death].

So of course there were also other types of confrontations involved, when they don’t get some things, they try to protest and all those types of things. They would go on strike etc. There were also other types of things we had to confront them [with]. Another time, they wanted something – I forgot what their demand was. I went into the camp and as I was going to leave the camp, there were three rows of women and children blocking the exit and not allowing me to leave, and basically taking me hostage. I was quite upset and told some of the staff accommodating me to push me out. They used the women and children in front because the men, male staff would normally avoid coming into contact with the women. And if you come into contact, or confrontation with children, you would be in great trouble. But the fact that I am a woman as well, I didn’t care about that. They just pushed me down. Then I went out of the camp, and that was a very unpleasant experience because if anything should develop, or intended to be a hostage situation that would leave a very bad taste in one’s mouth. So there are bits and pieces of those [sorts of stories]. There are quite a lot of these [incidents].

Another time, there was a lot of fighting in the camp. So there was one dormitory that we believed were the instigators. So we kept them separate, while all the other dormitories feared we closed that dormitory, not allowing them to come out. At that time, the UNHCR came, wanting to inspect the camp. We told them there was trouble, but then they of course could come into the camp and look [around]. And I had to go into that so-called troubled dormitory. And so I went in. It was unpleasant at the time, but one of my staff asked me afterwards if I was scared. I answered that I was worried, but not overly worried because I didn’t think I had done anything that would upset them so much that they would attack me. But that was quite an experience, walking into a camp with people who were segregated for creating trouble. But at that time, we didn’t want to disturb the action of the UNHCR. We wanted them to try and settle the problem as quickly as possible. So those were the types of things we encountered. It was unpleasant at that time, but afterwards, it didn’t really matter.

I: What were some of the trouble they [the refugees] caused? Could it be physical?

BW: Yes, they could be very violent. And the initial trouble was created between North and South Vietnamese. It was something I couldn’t understand, because how could they come out to find a life and why care about who comes from the North and who came from the South? They separated themselves so fiercely that they would always come into conflict and they would fight, often [leading to] a fatal attack. If they wanted to kill somebody, they would invariably succeed. And I thought about it, and they would easily fight. And I tried to find an explanation, and I thought my own thinking that there has been war for over twenty years. So when somebody just touches [you], you turn to see what happens. When we are not happy, we just start yelling. But if somebody touches them, they fear for their safety, for their life. Because that is how I’m trying to rationalise their actions. They fight and they are really fierce.

It’s not like prisoners fighting, it’s fist-fighting. They are not talking about wanting one’s life. But when they [the Vietnamese refugees] start fighting, it’s a matter of killing. There were lots of killings in the camps, it was unbelievable. So I am trying to rationalise their behaviour. And I thought it was because they were growing up in violence. Once they confront something, their first reaction was to fight back.

That is what I think. If you are in a camp or war situation like that, that is your first reaction which is not a normal reaction from somebody who has been in peace all their life. There’s lots of violence in the camps, so much that we had to separate the camps – one camp for North Vietnamese and another for South Vietnamese.

I: Were there weapons involved?

BW: They had lots of weapons. We provided them with water pipes in their camp. We provided them with bunks of which the frames were built with metal. They dismantled the metal [from the bunks] and their bunks wouldn’t stand properly. So they pushed all their bunks together, so instead of having space between the bunks, they pushed them together and put them in a central place to support each other. So they took out some of the frames to [make] weapons. The weapons they produced were fatal weapons.

I: Did they ever hurt the officers and the personnel on the Hong Kong side, or just among the Vietnamese?

BW: Mostly the Vietnamese. Very rarely they attacked the officers on duty. And I can also understand that because we are talking about the officers on duty are not people who just control them. They also provide them with their daily necessities, like food and providing medical care, taking them to the hospital if they’re not feeling well etc. So as human beings, some sort of relationship developed throughout this process. So basically, there is a basic understanding of one another. How an officer is like and whether he is a nasty one or not. And you can’t really be nasty in a camp of thousands, when only ten and twenty [officers] are on duty. So there is quite a peaceful relationship between them and the officers, which is very important, because you are talking about detaining a number of people constantly – 24 hours – for a certain period of time. In the process, there are ‘care’ issues.

For example, if someone died, we had welfare officers on duty to take care of the other parts of the family, to see how their emotions are and give them the proper support and that type of thing. And throughout that process, some sort of relationship invariably developed. So the attack against officers will only develop when hatred develops. But there will be reasons I believe for them to dislike us. To dislike the policy and what we do. But I don’t think there’s any good reason for them to hate us for the extent of attacking [the officers], unless they wanted to hold us hostage for a purpose. Like the other incident I mentioned – if they wanted to hold you hostage for something, that is they wanted to hold you hostage for a purpose – not because they disliked a person, but if you’re talking about attacking or harming that person it’s a completely different story.

I: Did they ever hold any other officers hostage?

BW: Yes. There was one time they held one officer hostage, which was in High Island Detention Centre. And I think everybody in the whole of Hong Kong was very upset. Because they hurt one officer, they made long spears as a homemade weapon which they pierced through an officer’s hand, disabling that officer’s hand for life. And then they held one officer hostage. They were very unhappy with the fact that some of them had to be repatriated to Vietnam, those who had failed to be screened in as refugees. So that was a long night, we had to save the officer. The officer came out unhurt, but it was quite a scary experience. We were also worried about the officer’s family as we had to keep in contact with the officer’s family as well. Fortunately, the officer’s father was very modest, saying he would trust us. He didn’t give us too much trouble. And the officer himself when he came out was quite peaceful. There weren’t a lot of grumbles in that hostage-taking situation.

I: How long did they keep him for?

BW: It happened about the time of the evening meal when it was being issued. And he was released in the early hours of the next day.

I: Do you remember when it happened?

BW: No, but there would be records showing that.

I: What were the consequences to the refugees in such instances?

BW: [There were]. No consequences. They were held in a dormitory. You cannot identify who held [the officer]. So basically this was the type of situation you couldn’t get the culprits. Basically there was nothing except you had to be more careful next time. But that doesn’t help the relationship between the staff and the refugees. It was more apprehension between the two parties, and they were more apprehensive and we needed to be more careful. Nothing really happened. You didn’t get the actual culprits and couldn’t punish the whole dormitory.

I: Approximately how many people died in the camp during your time?

BW: A lot. There were a lot of serious attacks and murders. They had water pipes and would sharpen one and stack them in one spot. And then they pulled them out, so that the blood would just drain out. And that was a very effective way of killing people. If they just pushed it in and let it stay, then probably it would be better, but they pulled [the water pipe] out so the blood would come out.

I: Would the figures [of deaths] be in the tens or hundreds?

BW: Hundreds at least, if not thousands. Not in one camp or any one period, but over the years.

I: What happened to the bodies? Were they buried or cremated?

BW: They were cremated. And then we would see what the family wanted. If they wanted to, they could keep the ashes and things.

I: How did the people in the camp cope with losses like that?

BW: The family members you mean?

I: On both levels; the family members as well as the people in the camp.

BW: It’s funny because they didn’t seem to mind, they seemed to accept this as a fact. They didn’t seem to mind. Actually, the staff mainly was more [concerned]. They worried the staff more than [themselves]. They didn’t appear to be very worried. At the time when it was North and South Vietnamese fighting, there would be a lot of [fighting]. When they were all classified as one region, then they didn’t seem to care. They just thought it was a fact of life. That’s how it appeared to me, not undue emotions coming [from them].

I: Among the casualties, were there women and children?

BW: No. They were [mostly] men. It appeared that there were some sorts of disgruntlement or arguments [between them]. Those who were attacked and killed were men, not women and children.

I: Were there any casualties due to illnesses, or medical reasons?

BW: Every now and then, yes. But then in all these casualties, we sent them to outside hospitals. For minor ailments, we had a hospital – what we called a sickbay in the camp – where they could stay and rest and we had doctors. In our own camps, meaning camps within Correctional Services buildings, we had our own medical offices. In every penal institution, we had the establishment for medical offices to be stationed in that penal institution. So if the camp was a conversion from the original correctional institution, there was a stationed medical officer ready. And these other camps, like Whitehead and High Island, we sometimes commissioned the medical officers from Red Cross and other places, other medical professionals to come in and take care of minor complaints from the residents. But for serious illnesses that happened in the middle of the night or during holidays, they were rushed out into the appropriate hospital.

I: Were there any particular diseases that may affect a group of refugees or individual cases? [Were there] cases of malaria etc.?

BW: No. The initial problem was hair lice. When they first arrived, hair lice were really bad. We had to set up a sanitation centre. They were kept there [initially], and then we had to take away the hair lice. That was the worst problem we had when we first had them.

I: Would you like to take a break?

BW: No. That is only a recollection of mine. I thought that it was a good idea for these things to be recorded, of what happened. But it’s just a version of an officer’s feelings and stories and encounters over the time when she worked with the Vietnamese migrants in Hong Kong. But there were a lot of things that at first I was very amazed. For instance, the birth rate in the camp was exceptionally high. So we had the family planning people in for birth control. They were not interested.

We tried to find out why they had funny theories [about birth]. They would say that if they gave birth to a child [in the camp], by the time the child was four years old he/she would be in kindergarten in the United States. I would question how they could know [for sure] they would be in the United States in four years’ time. And when you talk about resettlement, they weren’t interested in being resettled in any European countries, but only California [or other American states]. They didn’t even want to go on board a flight. To us it was quite amazing and we wondered what was wrong with them. They only wanted [to go to] America.

I: Did they get to go to the hospital to give birth?

BW: Of course. They delivered in the hospital.

I: Would the children receive residence or citizenship in Hong Kong?

BW: No. Because of that, I believe that there is a special law or pass that they do not have that right. But of course they registered their birth here. Their birth registry would record their birth. All births were done in proper hospitals and even post-natal appointments, ante-natal appointments were done by the proper hospital clinics.

I: What did the whole experience mean to you? How did it affect you?

BW: It didn’t affect me. You see that they make a lot of things from the material they get. And when you think about it, when you watch [them] and after you’ve been in the business long enough, you understand that it is human nature. For example if you read a book called ‘Life and Death in Shanghai’, it was written by a wife of an Ambassador who underwent cultural revolution in China. She went to prison for that, and describing her life in prison. And she was acquiring a lot of things that weren’t allowed in the prisons. So you see that a person in a desperate situation will make things for themselves out of the materials available. And you’d be amazed at the type of things they can make. They can just come up with amazing things. You wouldn’t imagine that you could make something like that, but when you are in a very deprived situation, you can make things like that. It’s just normal. No matter what the education, it’s not to say you are of a bad calibre so you would do things like that.

If the person desperately needs something, you would think of ways for them to make it out of the materials available to them at that time. I am not too upset with what they made out of the water pipes etc. available. I’m only sorry that they would damage [public property] because it would also affect their own safety and affect their daily life. But if you have been there long enough, you understand that for a lot of them, it’s just human nature. So it’s even more important that people in the business should really think about providing the necessities to people who are under detention or really deprived. It’s very important I think.

I: Is there anything else you would like to add?

BW: Not particularly. I’m just relating an experience. There would be a lot of other frontline staff when the influx was getting more and more serious in the later years, there are other frontline staff who actually handled the riots and disturbances and hostage situations. They would have stories to tell about their own feelings. For some, there were times when there were a few officers handling a few thousand Vietnamese coming to attack them with spears. And they had to stand there because there was no alternative. Because they couldn’t let them get out, so they had to stand there. And they probably had some sort of sentiments to tell.

I: Thank you very much.

BW: My pleasure.

Third interview

BW: And then when the screening policy came in, and then there were a lot of amazing things. Like two young people falling in love and living together. And then one family was screened out as refugees so they had to move out to an open camp. But he wouldn’t go because the girl was inside. Even moving them to an open camp could be an incident, you know. Then at the end of the day, we were asked to keep the person who wanted to stay voluntarily in a closed camp and his family could go to the open camp. So the young man or woman could stay. But when I took over as Assistant Commissioner, I said they had to go [the young man or woman in love] for the simple reason that we only could keep people under the authority of the law. We couldn’t keep people because they were willing to stay inside. And also, if some attack happens and there is violence or injury, where is the responsibility? I didn’t want to accept that responsibility. I mean, we had legal responsibilities to ensure their [the Vietnamese refugees’] safety. Any major injuries or death [that occurred] we would have to go through the death inquest, to go to the Coroner’s Court. I had to be liable to the life and death of this person. I couldn’t allow for someone who was willing to stay, to remain in camps like that. I said I wasn’t going to accept them. So there were a lot of confrontations between Departments.

I said the Immigration Department should have taken care of them, I didn’t care. I said they could take care of them and let the young man (or woman) leave because I wasn’t interested in letting them stay in the camp. Because there were a lot of other issues that I personally believed we shouldn’t have taken on. In case of serious injury or fatal incidents happening, there’s just not the type of responsibility that should be imposed on [us] as Officers. So that, again, aroused some sort of argument, or debate between Departments on what to do on [a situation like that]. Because they are allowed to stay on humanitarian grounds, I said ‘no way. These camps can only keep people under direction of the Law or Courts’. We couldn’t keep anyone who was willing [or wanted] to stay in the centre. For example, what if a ‘street sleeper’ wanted to stay [in the detention centre]? Do I keep him in for humanitarian reasons? No way. So when there are multi-departmental efforts like this, you’d come into this type [of issue].

Each one [was] guarding their own Department’s interests. And at the end of the day, the people would need to figure out what they wanted. But one would imagine that once given the status of refugees, you would want to leave. But that wasn’t the case in this incident. So what was I supposed to do? I had to force somebody out to let them free. When you first heard about this, this was real life. It actually happened. Detention for the young couple was nothing. They wanted to be together, you see. So this is when all human nature comes in. You see the values of individuals and types of things like that.

BW: So in one day, we shipped out 3000 and received 3000. You get very tired, just watching, never mind about the job. I was totally exhausted when I was supervising the movement [of the refugees]. I don’t know how the staff survived. Just supervising and watching. Unfortunately the officer who supervised that operation died. Otherwise I would get him to tell you the experience of how he shipped out 3000 and received 3000 in the same day.

I: I’m sure in difficult times there are also a lot of heroes.

BW: One of the funny stories – I consider funny – from the pier to the camp was a bit of a steep, winding road. So you put these people in, women, pregnant women, children on board. So how do you get them [up there]? You’d have to pack them into lorries. There’s not sufficient safety [management principles] on them. So he packed the car and told them to squat them. And he pushed everybody together so it was like a packed in [tightly] so they were safe and there was no movement at all. That looks as if it is a harsh treatment. But that is only so the children don’t get hurt. If they all squat down, the children were safe, the cars wouldn’t rock. So in those times, one can think of amazing ways to get the job done. And I admired those officers very much. But he died of a sudden death. He went for a medical check-up and when he was in the lift of the hospital, he had a heart attack. He was actually in the hospital and wasn’t safe even then.